On a hot summer’s night in June 1860, the heavy door of the insane asylum clanged shut behind Elizabeth Packard and she felt all hope desert her.

Because she was not mad. She was merely independent.

Yet according to 19th century psychiatry, female independence was madness. Elizabeth, a housewife and mother of six, had simply stood up to her domineering husband. As she would record in a defense of her sanity that she wrote while in the asylum, she’d insisted, “I, though a woman, have just as good a right to my opinion as my husband has to his”—but assertive women in those days were swiftly dispatched to asylums, institutionalized for causing “the greatest annoyances to the family” and for defying “all domestic control.” No wonder Elizabeth had found herself on the wrong side of a locked ward door in the Jacksonville Insane Asylum, in Illinois.

The received medical wisdom of the age was that assertive, ambitious women were unnatural, and therefore sick. For centuries, women’s natures had been thought inextricably linked to their reproductive organs and, over time, this supposedly scientific fact had evolved into the belief that it was natural for women to be fulfilled solely by being wives and mothers. When, in the 19th century, biological-based gender roles came to the fore (work and intellect for men, home and children for women), it was one small step for doctors to declare that any woman who rejected her submissive, domestic role was medically impaired. Said one doctor after visiting a girls’ school in 1858: “You seem to be training your girls for the lunatic asylum.” Women who studied or read—or who simply had minds of their own and a determination to use them—were demonstrating “eccentricity of conduct,” which meant they were “morally insane,” a diagnosis invented by James Cowles Prichard in 1835. They were to be locked away until they conformed to more natural, feminine behavior.

And it was easy for the men in their lives to do it. When Elizabeth’s husband looked into the matter, he found he could arrange his wife’s committal simply “by the request of the husband” and specifically “without the evidence of insanity required in other cases.” As Elizabeth Packard put it: “[My husband] placed me in this insane asylum fully determined I should have a thorough dressing down, or breaking in, before he should take me out.”

As Elizabeth assessed her situation, she saw starkly the future that awaited if she refused to submit. Many of her fellow patients were also sane, but had been at the asylum for years; one, guilty of “extreme jealousy,” was midway through a 16-year incarceration. Elizabeth’s compatriots had been committed for reading novels, for “hard study” and for “insane” behavior during the “change of life.” (A woman’s menstrual cycle alone could see her committed, suffering from “uterine derangement.” Period-related madness was so commonplace that doctors encouraged mothers to delay the onset of their daughters’ menses by making them take cold baths and abstain from meat and novels.)

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

So many women were committed alongside Elizabeth that the hospital was overcrowded, with 231 patients squeezed into its 8 wards, and another 240 patients on the waiting list. Luckily, chloroform and ether were particularly effective on “boisterous” women and therefore used to quiet them—in doctors’ words—“not only temporarily but permanently.” Many asylum superintendents thought restraints such as straightjackets “rarely…necessary among males,” yet it was standard for disobedient women to be constrained. And if drugs and straightjackets didn’t work, there was always surgery. Contemporary medical notes reveal that a 20-year-old woman who spent “much time in serious reading” and a 30-year-old wife who dared express “great distaste for her husband” were among those subjected to the latest treatment to cure female insanity: a clitoridectomy.

The theory ran that a woman’s sexual organs caused her madness, so cutting off her clitoris would calm her. Doctors claimed a 70% success rate. Other treatments of the era included removal of the ovaries, the injection of ice water inside intimate orifices, and the application of leeches and caustics to the genitals.

And there was only one way to escape: to submit.

Elizabeth Packard grasped the harsh reality: “If [women] remain, true to their natures, there is no hope for them.”

Every genuine emotion had to be stifled. Every act of difference from society’s prescribed model of femininity had to be suppressed. Elizabeth could not display her anger at what had happened or even hint at hatred for her husband. Her psychiatrist was watching—and her unladylike emotion would justify continued incarceration. After all, women who had “ungovernable” personalities and “strong resolution…plenty of what is termed nerve” were literally textbook examples of female insanity.

Nonetheless, Elizabeth wrote of the “breaking in” she was supposed to be experiencing: “I think it will be a long time before this cure will be effected.” Determined to remain true to herself, she wrote: “God grant, that the time may never wear away in me this spirit of resistance.”

And that spirit of resistance is something we all still need. Because the medicalization of female behavior didn’t stop in the 19th century. Nor did the attempt to silence and discredit women by claiming we were crazy.

Think of the fearless suffragists, who were deemed hysteric. One doctor declared: “There is mixed up with the woman’s movement much mental disorder.”

Think of Rose McGowan, whose resolve to hold Harvey Weinstein to account saw his lawyers discuss a plot to make her seem “increasingly unglued,” a memo revealed.

Think of Nancy Pelosi in her electric-blue suit literally standing up to Donald Trump. “There is…something wrong with her ‘upstairs,’” Trump railed on Twitter in response. “She is a very sick person!”

That hot summer night in 1860, Elizabeth thought her life was over. In fact, it was only just beginning. “The worst that my enemies can do…they have done, and I fear them no more,” she wrote of being locked up in the asylum. “I am now free to be true and honest…This woman-crushing machinery works the wrong way. The true woman shines brighter and brighter under the process, instead of being strangled.”

The patriarchy can try to control us, but some of us cannot be controlled. Instead, we can take inspiration from women like Elizabeth, a woman who—like so many others before her and long since—was declared insane by a patriarchal society simply for speaking her mind. Yet despite the odds being stacked against her, she managed to triumph and changed the world, improving the rights of women and the mentally ill.

“Women are made to fly and soar,” she wrote, “not to creep and crawl, as the haters of our sex want us to.”

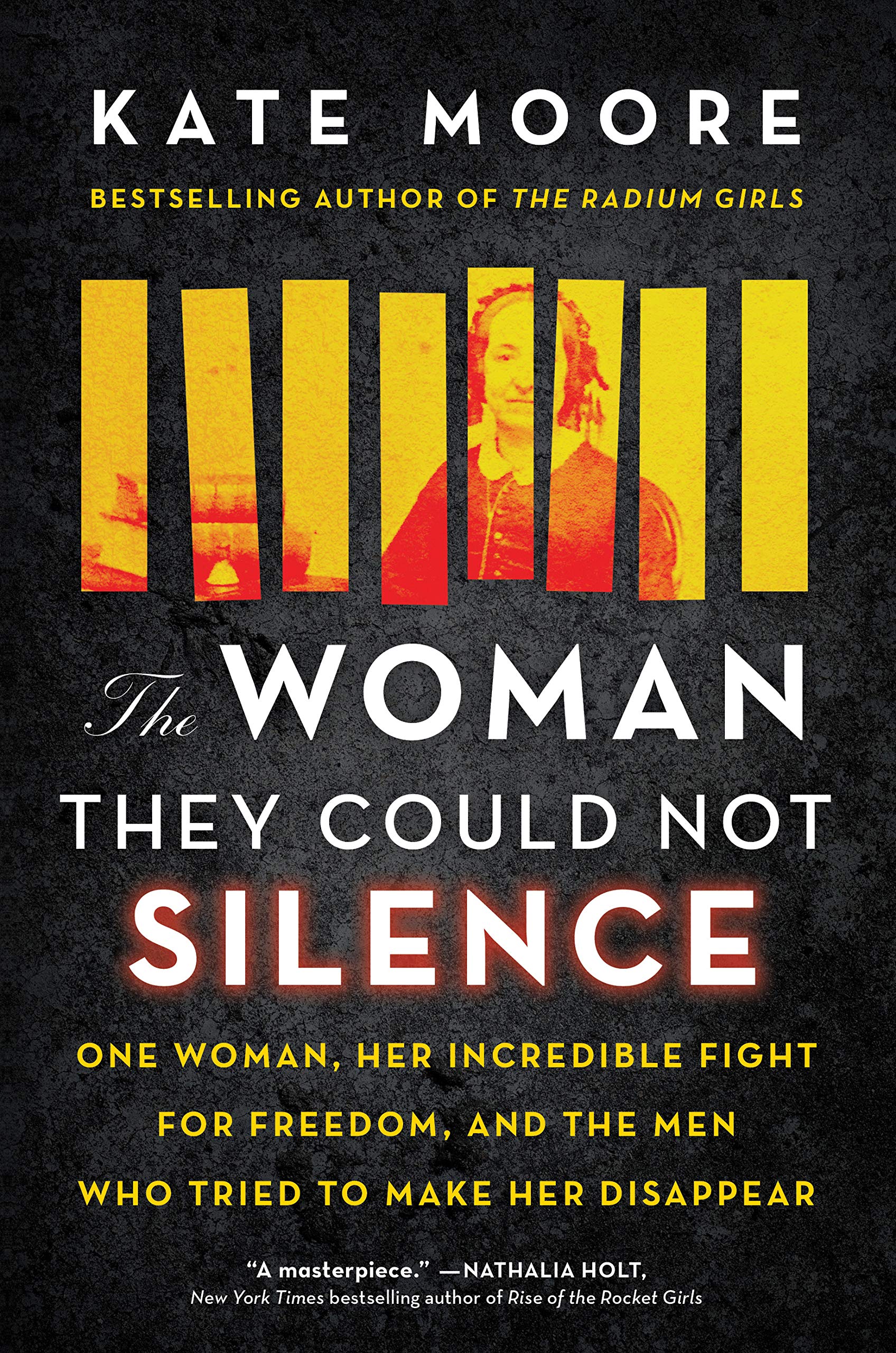

Moore is the author of The Woman They Could Not Silence, available now from Sourcebooks.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com